You and Your Designs

Towards a future of significance.

by Vitorio Miliano

, @vitor_io

Perhaps the central problem we face in all of [design] is how we are to get to the situation where we build on top of the work of others rather than redoing so much of it in a trivially different way.19

¶ 1 We are designers: part of a new breed of interdisciplinary folk, “part sketch artist, part programmer, with a dash of behavioral scientist thrown in”, who “are some of the most sought-after employees in technology”.20 If we’re web designers, our medium is pixels. If we’re user experience or interaction designers, our medium is time itself.21 Upon the strike of inspiration, we figure out how the rest of the world is to use technology, inventing systems that are innovative and intuitive.

¶ 2 We are designers: captains of industry! And captains of laying out these benefits analysis forms for a healthcare services portal—but just for the time being.22 We read that Smashing Magazine article on responsive web design23 and are proud of Ethan Marcotte for coming up with it,24 and we understand most of it. But our company is too conservative for that—IT’s starting to cave on iPads, but our firewall restrictions still make day-to-day work difficult.

¶ 3 We are designers, earning hundreds of millions of dollars for our companies.25 And while right now we’re editing these royalty-free stock photos into some daily deal ads, we also skimmed and bookmarked that article on the future of shopping carts.26 We don’t have a shopping cart, but we’ll know what to do if the need arises.

¶ 4 We are designers! And by “we” I mean “I,” since I’m the only in-house “new media” person in the whole company, and I don’t really know any others in town. But I’m sure I get so much freedom compared to those agency or product designers who always have someone telling them what to do. Somebody said design was all about constraints, right? This project is an interesting design constraint: I can pick any royalty-free stock photo I want, as long as both the boss and the client approve it. And as long as it costs only one credit.

¶ 5 We are designers, but we feel like we don’t do enough design. Even if we have it pretty good, we might not be doing enough research, or we’re missing out on mentoring, or we don’t get to do enough original work. Perhaps we say we don’t have enough time, or our company can’t afford it, or our clients won’t let us.

¶ 6 We are designers, and we’ve noticed the work we’ve done all year is all pretty much the same, and isn’t really worth putting in our portfolios. Perhaps we’ve been a little slack with our professional grooming. Maybe we have a blog, but we haven’t written a professional blog post in six months. We might not even have a portfolio if our work is all under NDA; what would we put in it anyway?

¶ 7 We are designers who think maybe the marketplace needs to slow down a little. We only just got all this CSS figured out; what’s LESS and SASS? We don’t know enough math to make these crazy 3D CSS transforms. We write off WebGL, hoping it will only be important for JavaScript programmers. Sure, we saw multitouch in the movies,27 and then in that TED talk,28 but we didn’t really expect there to be a phone that used it a year later;29 certainly this Kinect gesture thing is only for video games.

¶ 8 We are designers, making excuses for ourselves.

¶ 9 And we’re not alone. By every measure,30 only a quarter to a third of us freelance, meaning most designers are having these experiences right now. For every Ethan Marcotte and Jeff Han, there are as many or more unsung, in-house designers toiling away on unnamed enterprise applications.31

¶ 10 Ethan Marcotte invented an entirely new way of building web sites—and then went independent.32 Jeff Han invented entirely new hardware technology—and fended off investment offers.33 We are designers, but we can’t all build the future, can we?

¶ 11 You’re not alone in your unease with your professional efforts. You’re not alone in what you feel is wrong with our job. And Ethan Marcotte and Jeff Han are not alone in their ability to invent the future. Let’s talk about what we’re missing, and then discuss how we can improve.

What we’re missing

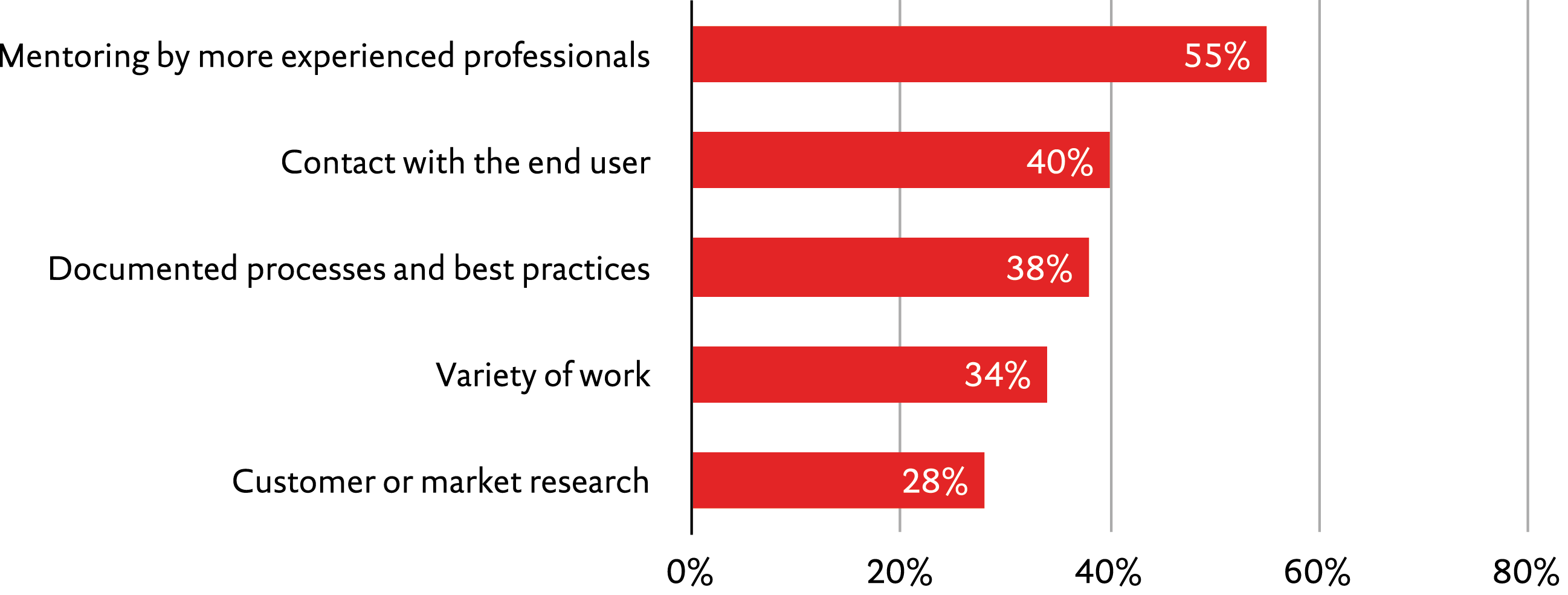

¶ 12 In Austin, TX, for the past two years,34 we’ve asked local designers, “What are you missing in the professional practice in your workplace?” In 2012, the top five responses look like this:35

¶ 13 More than half of us wish we had mentors, meaning we aren’t getting the validation, oversight, and training we think we need. Two-fifths of us want more contact with our users, meaning we don’t have enough confidence that our design process is appropriately user-centered. Over a third of us don’t have reliable best practices or internal processes, and another third wishes we did different work.

¶ 14 The former third isn’t able to effectively repeat their strategies or train others: they’re winging it. The latter third aspires to something different, and it’s not necessarily a grass-is-greener situation. Companies have business needs and hire to solve those specific problems; whether you’re a screenwriter36 or a Java programmer,37 once you have a track record doing something in particular, it’s in an employer’s near-term best interest to keep you doing that. An in-house designer who executed a CMS administration interface well is going to get to do more of them; an agency designer might find themselves the reason their company sells a lot more similar projects, too.

¶ 15 Over a quarter of us can’t be sure we’re designing the right product, because we’re being asked to work without any market research. Research is the foundation of user-centered design, and even if you’re practicing some other methodology, they all start out the same: “Design activity can’t take place without some definition of the problem to be solved and how we might go about solving that problem. These parts of the design process are generally covered by research and analysis.”38

¶ 16 These missing five needs are fundamental to an effective design process. We’re not “magical creatives” who “succeed based on instinct, rolling the dice every time, rather than on a methodical process that can be repeated time and time again. […] People get to where they are in life by following a process… Your successful process has also led you to enough good work that people want to keep hiring you to do more work.”39 Because these figures are self-reported, they’re also underreported: you have to be self-aware enough to know that you should have a mentor, or that you shouldn’t be designing in a vacuum. Many designers don’t even realize they’re missing these things, and in our survey, nearly 6% said as much. In actuality, everyone should have a mentor, for example: junior people should be mentored by senior people, senior people should be mentored by leads and architects, and leads and architects should be mentored by business development folks and also by the junior folks who are into new technologies so they don’t lose their edge. All of these are basic process requirements, and a quarter to half of us are being told, in some manner, shape or form, that our process needs to get stuffed.

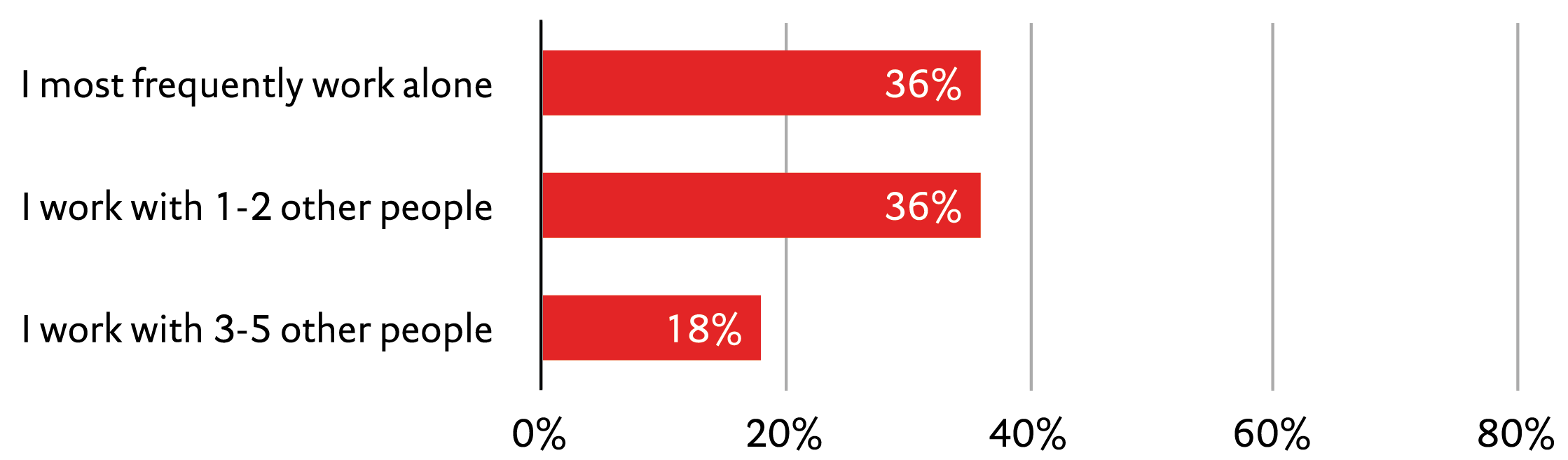

¶ 17 Our survey also asked, “How many designers do you collaborate with regularly?”

It appears that we usually work alone. A full third of us get no regular interaction with other designers, and another third only interact with one or two people. Working in isolation makes it nearly impossible to bounce ideas off of each other, and working with only one or two people breeds a routine that results in creative ruts. The best work—whether brainstorming or production—comes out of a diversity of personal experience,40 a diversity of interpersonal interaction,41,42 with the oversight of a mentor,43 and with everyone physically nearby.44

¶ 18 Some of us try to fill in these gaps online, but it’s hard to explain a UX problem and its context in 140 characters. From the A List Apart surveys,45 we know around 75% of designers have a blog or personal site—but not how often they write about design, nor how often they write about shipped work versus casual experiments. We know that when friends get new jobs, significant others,46 or children, their free time decreases and their writing is often an early casualty.

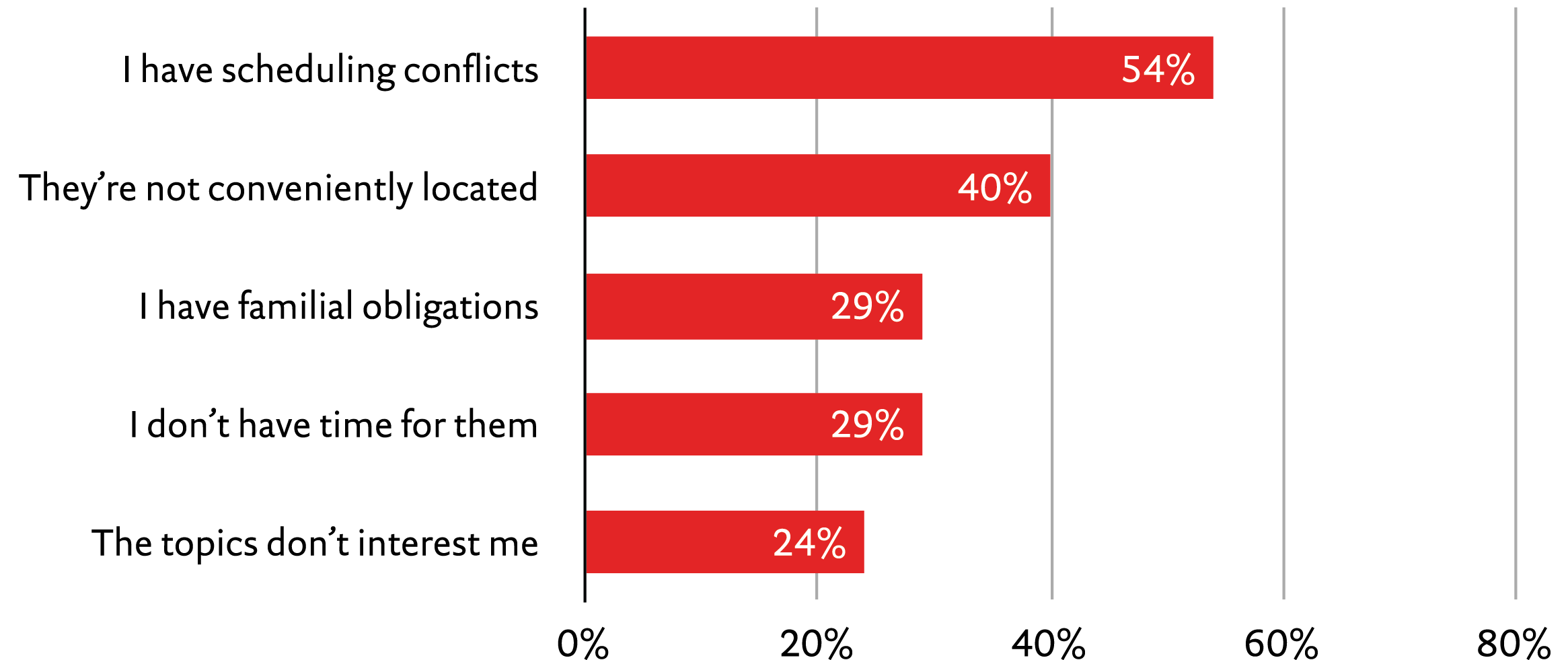

¶ 19 ALA doesn’t ask about ongoing writing for blogs, and we didn’t ask for that data in our survey, but if we consider blogging to be an extracurricular activity like attending a local design meetup, we can infer those effects from the top five responses to a similar question: “Maybe you’ve missed out on local community events. Why is that?”

¶ 20 Over half reported scheduling conflicts: whether from meetups scheduled at the same time or more important or better things to do, we’re busy, and we get busier the longer we’re in the industry. Two-fifths claim geographic inconvenience: for many, extending the workday an hour or two for a professional meeting nearby isn’t unreasonable, but if it’s in the opposite direction from home in rush hour traffic, it’s a lost cause. Professional support activities, like any application we design, are more usable if they fit into the patterns of things we already know and do. The excuse of being busy surfaces again, as just under a third report family time or no time at all as factors. Finally, a quarter of us report that the topics aren’t interesting. If we can’t talk (or blog) about work because we’re under NDA, and if everyone else is, too, what is there to talk about? Finding professional support in that environment may seem hopeless.

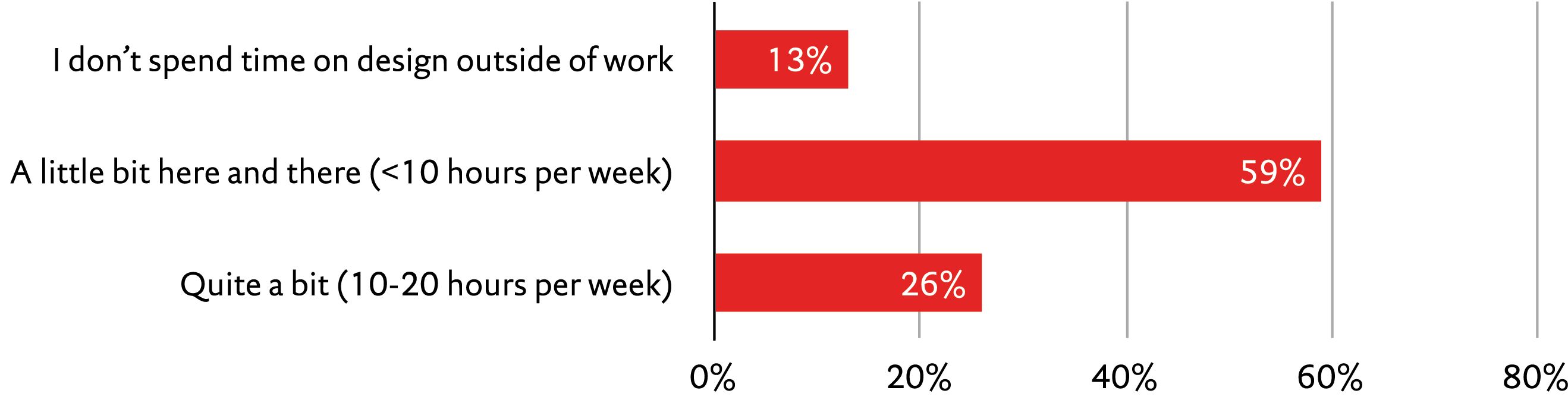

¶ 21 If we’re not getting the professional support we need from our day jobs, we should be making it up outside of work if we expect to improve as designers. Do we? We asked, “How much time do you spend on design outside of your workday?”

Nearly two-thirds of us spend under ten hours a week on design outside the office, and over ten percent of us spend no time at all. This isn’t, by itself, damning. If that time was spent with mentors, or on deliberate or slow practice of design techniques, or on rigorous study of best practices, it could be enough for us to grow.

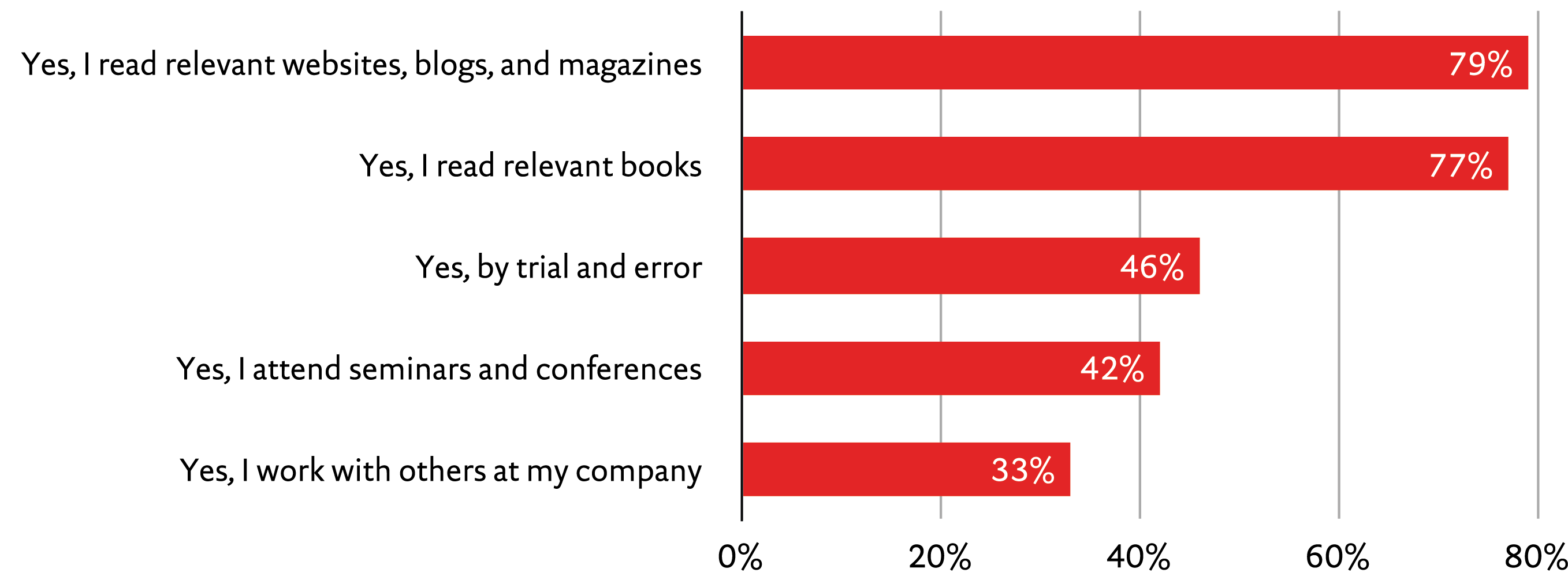

¶ 22 To find out if we spend our time as best as possible, we also asked, “Do you study design?”47

Investing more time is the number one driver for expert performance, but our top two preferences are overwhelmingly in favor of passive learning. The trouble here is twofold: under ten hours a week doesn’t give us enough time to learn new things, and passive learning doesn’t give us experience. We don’t spend enough time doing the right kind of practice to make the difference between understanding a problem and solving it quickly, and only being able to solve it if someone’s already written a blog post about it. Knowing CSS’s ideal rendering won’t teach you about cross-browser subtleties; likewise, being able to dig up an answer through search engines and Stack Overflow isn’t the same as comprehending the underlying fundamentals. Nearly half of us report that we also learn by “trial and error”, but it’s not clear if that means “copy and pasting examples until it kinda does what I want” or “rigorous testing and experimentation to thoroughly understand the material”.

¶ 23 These specific examples call out things that we’re all bad at to some degree. Whether you’re managing a team without a process, or you’re a recent graduate who doesn’t participate in your local community, a substantial portion of the designer population is just like you. Almost nobody is building the future, because almost nobody has the grounding for it, nor takes the time for it.

¶ 24 But you can take steps to remedy this. All of these examples are rooted in two core issues: not enough sharing with other designers, whether in the form of a mentoring relationship or a critiquing process; and not spending enough time on professional development, whether following a good process or making the effort to dig into a design subject. These examples call out what holds us back as designers. These are the practices that keep us editing royalty-free stock photos into daily deal ads instead of researching and inventing new interactions for new technologies. We don’t need Ethan Marcotte or Jeff Han to tell us how the future should work. We can find it for ourselves, and tell them about it the next time around.

What we’re finding

¶ 25 We cited responsive web design earlier as a new way of thinking about web design—launched just a couple of months after the iPad. While timely, Ethan Marcotte had been laying the groundwork for responsive web design for at least a year, with articles on fluid grids48 and fluid images49 and a book on “handcrafted” CSS.50 But you can’t handcraft something without deeply understanding its nuances. The invention of responsive web design is a great example of how “putting in the time” can lead to something bigger. Marcotte shared his work, dove deep into the subject, and was well-poised to make the proposal after the iPad’s launch. How you work makes the difference between just working and working significantly.

¶ 26 Scientists and artists have shared quips like “chance favors the prepared mind”51 for hundreds of years, and research now backs them up. Innovation, creativity, and expert performance do not spring from innate talents. Studies on innovation boil it down to markets, business values, and customer needs, but creativity is more a matter of meaningfully recombining elements from one’s experience. Likewise, expert creative performance is not a factor of innate ability, but one’s practice regimen. We can study markets to find undiscovered, disruptive innovations. We can share our work early and often. We’ll do better work if we practice our craft, try different methods, and learn the precise details of how our work is realized. This provides us with the foundation to make better work.

¶ 27 But the best work on enterprise software won’t help us invent the future. We have to work on important problems—even if we’re not able to work on them all the time. By the numbers, most designers find their work “exciting”,52 but being challenged by unusual constraints, or building for a brand name, are not the same as working on important problems. And to my knowledge, nobody has surveyed designers to see if they are excited because they’re working on anything with long-term importance.

¶ 28 Ask yourself, “What are the most important design problems today?” and “Which of these problems am I working on?” Learn enough to find the answers, and then put yourself in a position to answer them—if not through your day job, then in your off hours.

Five important problems

¶ 29 What makes a problem important? It’s not the end result: responsive web design provides a new way to build sites, but it’s not the only way. Rather, importance is a factor of solvability: important problems are answerable, if only you could connect the right dots. Important problems advance understanding. Marcotte figured out how to unify design rhetoric across many devices, but he probably didn’t know he was going to get there when he started in 2009: the iPad didn’t exist yet, and neither his articles nor his book mention “iPhone” or “mobile” or even just “phone” in a relevant context.53

¶ 30 You can’t know exactly what field to work in, but you can stay active in places where something might happen. Maybe these places are where the work is diligent rather than sexy—like documenting the history of interaction design, saving rare hardware, or preserving old books. Maybe they are social and cultural, like educating designers on the value of professional practices, designing supportive professional societies, and building tools for study. Or maybe the future will be built on defining best practices for future tools and their interactions. Wherever you see important problems, you’ll do great work by sharing your explorations with others.

Responsive web design

¶ 31 As a response to the onslaught of new screen resolutions and dimensions, “responsive web design” has gained an enormous amount of attention in a very short amount of time. Attendees of An Event Apart 2012 felt it was heavily dedicated to it.54 Major newspaper sites, never ones to take technological leaps, have redesigned with responsive layouts.55 But designers and clients have struggled to find a workable responsive design process. Responsive web design is an important problem, not because it’s the be-all, end-all technical solution to the multi-device, multi-screen problem (it isn’t and shouldn’t be), but because it exposes content and content management as a first-order design constraint. The tools, processes and practices to support content management for a responsive web design—and for whatever will replace it—are where designers now need to focus their attention.

¶ 32 Traditional web design processes evolved from two-dimensional print layout. Sketches and wireframes assume fixed proportions. While a site’s information architecture makes no such assumptions, a visual layout must take up a certain amount of space by definition. Drawings must necessarily show a fixed moment in time; they cannot demonstrate the breakpoints of a responsive design. A designer could produce storyboards or motion graphics; a designer with development skills could build an interactive prototype. Popular wireframing tool Balsamiq recently wrote about experimental ways to use their software to prototype responsive designs: repeat the work three times.56 As their software is a drawing tool, it can’t support illustrating transitions, meaning that subtle changes between display sizes or resolutions must be conveyed differently. Rather than illustrate every possible state in every way possible, they suggest producing high-level templates.

¶ 33 Responsive designs pose challenges for content strategists as well, as they require different content approaches for each breakpoint. Shorter headlines, summarized copy, and different hierarchies pose new challenges. Speaker and designer Karen McGrane illustrated the problems57 when a print-centric design mindset collides with a new technology, contrasting Condé Nast’s repeated failures of their iPad apps58 to the comparative success NPR has seen with their “COPE” approach, which slices content in the CMS to fit multiple formats ahead of time.59 In McGrane’s presentation, “Adapting Ourselves to Adaptive Content,” she holds up the venerable TV Guide as one of the most foresighted of media organizations, for each episode description was written three times—short, medium, and long—and they licensed their database to cable and satellite companies, enabling TV Guide listings to be embedded as a person channel surfed. TV Guide-the-magazine became unprofitable, but the database—three formats for every show ever, forever—became successful. NPR redesigned their process from scratch to succeed, putting them ahead of Condé Nast. With responsive design and flexible content, designers need to work deeply with information architects, content strategists, copywriters and engineers to design novel approaches which pay off.

A/B testing

¶ 34 A/B testing was invented by marketer Richard Stanton in the 1930s as split-run testing,60 where a newspaper or magazine would split its press run to print two different versions of an ad, allowing response rates to be tested within a single demographic pool. This sort of test marketing and copy research was pioneered by Claude Hopkins,61 the first to describe practices around vetting ads and products in small markets before a mass launch, and to iteratively try different headlines, formats, pitches, copy and targeting, in his 1923 book Scientific Advertising.62 So influential was this work that advertising magnate David Ogilvy introduced a new edition, saying:

Nobody, at any level, should be allowed to have anything to do with advertising until he has read this book seven times.63

¶ 35 Today, most A/B testing of web and interactive content still works like a 1930s split-run test: two different designs, pieces of content, or calls to action are produced. Half of your visitors see one, half see the other, and the most successful version wins. Designers often see A/B testing as useful only for settling minor design disputes; marketers use it to optimize copy; non-design savvy organizations use it to make decisions, such as when Google tested 41 shades of blue.64

¶ 36 For decades, A/B testing has been used to find the most compelling and actionable solution, but few designers pursue it like the best advertising firms do. It’s an important problem, not because it’s new, but because intentionally and purposefully trying different things goes against how many of us were raised as designers. Steve Jobs quotes Paul Rand as bristling over the idea of trying different things for the NeXT logo design:

I asked him if he would come up with a few options. And he said, “No, I will solve your problem for you, and you will pay me. And you don’t have to use the solution—if you want options, go talk to other people. But I’ll solve your problem for you the best way I know how, and you use it or not, that’s up to you—you’re the client—but you pay me.”65

Our future hinges on our confidence to design entirely toward a goal,66 including dramatic changes, not only small iterations or aping trends. Marketer Lance Jones calls this out:

Tweaking an existing design based on ‘best practices’ or recently-blogged-about split test results may result in a better design, but it won’t likely come close to the best design. ...you need to be open to designing bigger, bolder experiments—such as long copy vs. short copy, image heavy vs. text heavy, sales tone vs. academic tone, or process value focus vs. product value focus—before you conduct iterative tests on an existing design.67

¶ 37 It’s an important problem because distrust of A/B testing is widespread. For example, Jamie Dihiansan of 37signals wrote:

Maybe we don’t want to be second-guessed. Maybe we don’t want to cater to the lowest common denominator. Designers are taught—explicitly and implicitly—to follow certain visual rules and the final design will work great. The whole A/B testing concept probably came from from “strategy analysts” or “MBAsses”.68

Jamie Dihiansan had come from Crate and Barrel, a store that puts every corporate team member on a retail store’s sales floor for two weeks.69 Retail stores are experts in the subtle marketing pushes that drive us to buy one thing over another. From the distance between aisles to the specific cents on a price, nothing is arbitrarily determined. Dihiansan continues: “most designers out there design something to sell something else … the best way to communicate something better is to understand what customers need or what they’re looking for.”70 What better way to understand than to try different approaches and see what works? That’s what all the sales people around him would have been doing.

¶ 38 Three years after Dihiansan joined, 37signals decided to A/B test radically different designs for their marketing sites, starting with a long-form, “sales letter-style” approach, a direct marketing standby that many designers criticize as scammy. 37signals’ sign-up rate increased by 37.5%.71

¶ 39 Another radically different design was tried, and provided a 47% increase in paid sign-ups over the long-form sales letter. This made for a 102.5% improvement over the original site.72 37signals doubled their sign-ups, and all they had to do was admit they were eighty-eight years behind the times on marketing. Only by setting aside our classical notions of what it means to design, will we be able to design selflessly,73 fully in the service of our goals.

The Internet of Things

¶ 40 During his seven years with Apple, Tony Fadell led the design and development of the iPod. After leaving in 2008, he launched the Nest:74 a networked home thermostat that learns your HVAC system’s performance and your temperature preferences, adjusting your home’s climate accordingly. The Nest is part of a new category of devices in the Internet of Things, where common objects gain three additional properties: they know their internal or external state through sensors, they are uniquely addressable, and they are networked to each other. The Nest knows your HVAC system’s state and your house’s temperature, multiple Nests in a single home work together but can be checked independently, and they all connect over wifi. Through the Nest, your HVAC system is effectively connected to the internet.

¶ 41 Internet of Things devices can be classed by their connection type: smart or dumb. Like the terminals of fifty-year-old mainframe computers, dumb IoT devices require an outside agent to read their sensor data; they can’t ping the outside world on their own. For example, a dumb front door couldn’t tell you that someone’s knocking right now: it can only tell you how many knocks there have been since the last time you checked. Or, a dumb dress shirt could only tell you someone has spilled something on it when you ask.

¶ 42 A smart IoT device, on the other hand, can make connections on its own in response to user or sensor input. For example, the Nest can phone home to check for upgrades, and long-term data usage is reported back to Nest’s “Energy History” service. A smart front door could tell you someone is knocking right now; equipped with a camera, it could send you their picture. A smart washing machine could ask a dumb dress shirt how dirty it is, look up each garment manufacturer’s recommended washing instructions, tell you how long the wash cycle will take, and text you when it’s done.

¶ 43 While this may sound like an old vision of the internet, you can buy the Nest at your hardware store today. Companies, like ex-iPhone engineer Hugo Fiennes’ Electric Imp,75 are building hardware and software platforms to pass data between devices. Other firms are focused on smart or dumb sensors—or, like Toys for Bob,76 dumb toys that collect data as you progress in a video game. That game, Skylanders: Spyro’s Adventure, mixes the collectable nature of miniature toy figures with the Internet of Things into a 3D video game. You place a toy on the game console and play as that character. Game progress is saved in the toy itself, making it a dumb sensor that’s read by a smart one.

¶ 44 Whether they have smart or dumb network connections, the constants are that you can talk to each object individually (the “uniquely addressable” part), and they know their state (through sensors). Everything else you read about or experiment with the Internet of Things is emergent from these three properties.

¶ 45 By having a sense of their own state, and being able to communicate it, electronic devices can become self-evident. The Nest turns HVAC from an opaque system of furnaces and condensers and ductwork into something that can describe what it is doing. The Skylanders toys aren’t pointers to past gameplay; they are their own histories. This is why the Internet of Things is an important problem in design: it means we can do away with metaphors and have physical objects that contain their own meaning.77 The Internet of Things is still mostly dominated by electrical and mechanical engineers, and software for their data collection services tend to resemble a spreadsheet, rather than an iPhone app. The focus is on the technology and not on the use cases. We don’t yet know all the ways we can remake our tools and appliances given these new properties. And, we still lack a tested, trusted framework for conceptualizing the possibilities for interaction in a world where our household appliances can talk with each other, and with us.

Big data and Computational X78

¶ 46 Toys and thermostats aren’t the only places for advanced software and big data. Recently, the most famous example of the co-mingling of data and design is the iOS app Dark Sky,79 which does what most meteorologists never could: it accurately predicts the weather. It constrains itself by predicting only the next hour, answering the question: will I need an umbrella between now and when I get to my destination? Dark Sky downloads and processes weather data from NOAA, and renders a next-60-minutes radar map directly on your phone. There’s no cloud computing or subscription software involved. The math and graphics are so strenuous, only the latest two generations of iOS are supported. As a designer, how does one build a weather app that can predict the future without knowing all of the details?

¶ 47 “Inventing is weird because you have to create for a world which doesn’t exist yet,” speaks Matt Webb in 2010 to Mobile Monday Amsterdam.80 He’s trying to predict the future in this talk, a Dark Sky for an entire industry. He elaborates on some of the technologies I’ve named here, and points out: “all of these are just technologies... [they] don’t give us any clues for how to design for them, how to design these future media and services, and how we as humans relate to these things.”81 Webb goes on to provide four clues he’s found. The second he listed was hard math for trivial things—like Dark Sky, or his favorite example, Sudoku Grab.82 Sudoku Grab is an iPhone app that uses your camera to recognize a sudoku game on paper, and then it uses neural networks to recognize the printed numbers and overlays the puzzle’s answer on your phone’s screen. Sudoku Grab is a puzzle solver where all you have to do is point your phone’s camera at the puzzle. It’s perhaps the simplest, easiest, most efficient interface for a puzzle solver possible—no UI at all, just look —but how can you design that if you don’t understand three different kinds of math?

¶ 48 Webb continues, describing a BBC recommendation site that scrapes a hundred million blogs and all of Twitter:

It builds an internal predictive model of how much discussion that programme is going to get, it learns over time, and then it tells you, at the top, which one is getting the most discussion and says you should watch that. We employed a guy who writes fraud prevention algorithms for VISA. What?! This statistical technique was only invented fifteen years ago, it was only possible to make run on a server [instead of a mainframe] five years ago, and now we’re running it four times a day? I don’t know what’s going on in this world, but the fact that we can point the global computing capacity of fifteen years ago at really trivial problems is an interesting clue.83

¶ 49 Big data and computational X are important problems for design because they represent the event horizon for designer-as-polymath. Right now, a designer building a basic iPhone application can do it all themselves: design, graphics, programming (albeit slower than having expert coworkers). But, what designer has enough of a background in physics, in neural networks, in computer vision, in GPU programming and in machine learning84 to build Dark Sky single-handedly? As a profession, as an industry, as a community, we will never advance beyond the time and ability of a single person unless we stop trying to do everything ourselves and instead share, not just with other designers, but with other professions.

Immersive I/O and natural user interfaces

¶ 50 Frequently, science fiction films are consumers’ first look at the future, but the “future’s” interfaces are designed by motion graphics artists to look good on the big screen. We saw gestural interfaces in 2002 with Minority Report; four years later, we had the Nintendo Wii. The Kinect is now available for PCs, and the Leap motion controller is launching next year.85 Leap made a splash with its initial advertisement video,86 demonstrating greater precision than the Kinect in a smaller package, for a lower price. We saw multi-touch in 2005 with The Island; a year later, we had Jeff Han’s presentation at TED,87 and a year after that, Apple launched the first iPhone.

¶ 51 Immersive, 3D, virtual reality headsets have represented the future for over 20 years. Consumers have seen them in movies from The Lawnmower Man and Hackers to Disclosure and Runaway Bride. The new Oculus Rift headset88 is the first consumer-targeted VR headset in years, and it has the interest and support of every major video game studio. These studios see it as not just a possible future for video games but, from a design and development perspective, a necessary predecessor to augmented reality systems like Google Glass.89 The Rift, like the Leap, is already shipping hardware to select parties, but those parties are software developers, not designers. New technologies are often first developed by engineers and researchers, with no designers to study users or analyze market fit.

¶ 52 The Wii, Kinect, iPhone, and iPad have all been successful, but many of us haven’t designed multi-touch UIs or worked with gesture controls, despite their mass market availability for the past five years. Immersive input/output devices and natural user interfaces are important problems in design because they remove our “sensory deprived and physically limited”90 constraints on interactions with technology. Current visual displays give us a 2D viewport into our digital world at various sizes and resolutions; the Rift offers a 3D space, encompassing our entire field of vision, our view shifting as we move and turn our heads. Keyboards and mice only support an indirect manipulation of intangible representations;91 the Leap allows for direct manipulation with mimetic gestures, rather than symbolic actions,92 and the Kinect supports the same for our entire body. Anthropometrics, ergonomics and physiology can no longer be the exclusive realm of industrial designers; to build interactions involving the subtle interplay between a flick of the finger and a nod of the head in a 3D space, interaction designers must understand them, too.

Left as an exercise for the reader

¶ 53 Early drafts of this essay provided explicit recommendations on ways to share work, to be more professional, on prototyping techniques, and how to play with new technologies, but the specifics of these activities don’t really matter. All that matters is that you start—and keep doing it. You’ll have to fight new battles with yourself, your company, and your coworkers about sharing, professionalism, and what constitute important design problems. Those efforts will be hard enough without worrying about “doing it right.” Instead, just start, and you can improve your habits once they actually become habits.93

¶ 54 These problems touch baby sciences and new moons,94 and there’s a lot of territory over which to get discouraged. You may not be able to understand the problem space until you actively seek out peers in other disciplines. Collaboration will be vitally important; you’ll never advance the art if you try to learn everything from scratch. You’ll need to find people who understand the internal politics of publishing, or the psychology of consumers, or Arduinos, or algorithms—and who know that things can be better, that more can be done than is currently being done. Otherwise, that’s a lot of learning, and you’re not going to be able to do it all yourself. We can’t improve as a design community, as an industry, if we all start from the same place. We have to trust each other and build upon each others’ work. Make friends and play together.95

19. R. W. Hamming, “One Man’s View of Computer Science”, Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery, 16(1):3–12, Jan 1969.

The title of this essay also comes from Dr. Richard W. Hamming. His speech, “You and Your Research,” given at Bell Labs in 1986, was a turning point for me as a professional, and portions of this essay are nothing more than a crude, design-tailored paraphrase. The quote is from his 1968 essay on the state of the field of computer science.

20. Gerry Shih, “In Silicon Valley, designers emerge as rock stars”, Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/13/us-designers-startup-idUSBRE83C0QG20120413.

21. While intended to be hyperbolic here, an unnamed designer argued for this during a Q&A at Interaction11, against keynote speaker Richard Buchanan. Maria Cordell and Dave Malouf have also presented on time as our material over the years. Katie McCurdy, “Interaction 11 recap”, Sensical. http://sensical.wordpress.com/2011/02/28/interaction-11/. Maria Cordell, “Interaction Design for the Fourth Dimension,” IxDA. http://www.ixda.org/resources/maria-cordell-interaction-design-fourth-dimension. Dave Malouf, “Foundations of Interaction Design,” Boxes and Arrows. http://www.boxesandarrows.com/view/foundations-of. Also related: Paul Ford, “10 Timeframes”, Contents. http://contentsmagazine.com/articles/10-timeframes/.

22. “There are shop boys, and there are boys who just happen to work in a shop for the time being.” —Yvaine from Stardust (DVD, directed by Matthew Vaughn, Paramount, 2007).

23. Kayla Knight, “Responsive Web Design: What It Is and How To Use It”, Smashing Magazine, 12 Jan 2011. http://coding.smashingmagazine.com/2011/01/12/guidelines-for-responsive-web-design/.

24. Ethan Marcotte, “Responsive Web Design”, A List Apart, 25 May 2010. http://www.alistapart.com/articles/responsive-web-design/.

25. Jared M. Spool, “The $300 Million Button”, User Interface Engineering, 14 Jan 2009. https://articles.uie.com/three_hund_million_button/.

26. Luke Wroblewski, “Evolving E-commerce Checkout”, LukeW, 3 Jul 2012. http://www.lukew.com/ff/entry.asp?1579.

27. The Island (DVD), directed by Michael Bay, Dreamworks, 2005.

28. Jeff Han, “Jeff Han demos his breakthrough touchscreen”, TED. http://www.ted.com/talks/jeff_han_demos_his_breakthrough_touchscreen.html.

29. The TED talk occurred February 2006. The iPhone was announced January 2007 and released June 2007.

30. We talk about other sources in the next footnote, but even the stodgy US Government claims 29% of graphic designers were self-employed in 2010. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, “Graphic Designers”, Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2012–2013 Edition. http://www.bls.gov/ooh/arts-and-design/graphic-designers.htm#tab-3.

31. How many designers, precisely, is hard to say. AIGA states, “More than half of all professional designers in the United States are employed full-time by corporations and organizations”, but cites no sources, and agencies and consultancies may be included in that figure. In 2010, the UK Design Council found 36% of designers worked in-house (against 36% agency and 28% freelance), but only estimated against firms with over 100 employees, suggesting an underestimation. A List Apart’s survey that same year found only 27.8% of designers were employees (not partners or owners) of a non-agency/consultancy. However, ALA’s 2011 survey found 53% of designers were employees (not partners or owners) of a non-agency/consultancy. AIGA, “AIGA’s In-House Initiative”, AIGA. http://www.aiga.org/inhouse-initiative/. Design Council, “UK Design Industry Overview”, Design Industry Research 2010. http://www.designcouncil.org.uk/Documents/Documents/Publications/Research/DesignIndustryResearch2010/DesignIndustryResearch2010_UKoverview.pdf. A List Apart, “Findings from The Survey For People Who Make Websites 2010”, calculations by the author. http://aneventapart.com/alasurvey2010/add.html. A List Apart, “Findings from The Survey For People Who Make Websites 2011”, calculations by the author. http://aneventapart.com/alasurvey2011/add.html.

32. Ethan Marcotte, “Oversewing”, Unstoppable Robot Ninja. http://unstoppablerobotninja.com/entry/oversewing/.

33. Kim Zetter, “TED: Jeff Han, A Year Later”, Wired News. http://www.wired.com/techbiz/people/news/2007/03/72905.

34. Results from the 2011 survey are available at http://vitor.io/austin-annual-report-2011. Results from the 2012 survey are as-yet unpublished.

35. Designers could pick multiple options.

36. Scott Myers, “The Business of Screenwriting: They will pigeonhole you (and why this can be a good thing”, Go Into The Story, 18 Aug 2011. http://gointothestory.blcklst.com/2011/08/business-of-screenwriting-you-will-be.html.

37. Sean Landis, “On Avoiding Being Pigeonholed”, Artima Developer, 29 Mar 2004. http://www.artima.com/weblogs/viewpost.jsp?thread=41453.

38. Jon Whipple, “What Designers Know”, Distance 01:10–11. Recently available online at http://distance.cc/issues/01/01b-Jon-Whipple.html.

39. Mike Monteiro, Design Is a Job (epub), A Book Apart, 2012, chapters 1 and 6.

40. Gary Wolf, “Steve Jobs: The Next Insanely Great Thing”, Wired 4(2), Feb 1996. http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/4.02/jobs.html.

41. Brian Uzzi and Jarrett Spiro, “Collaboration and Creativity: The Small World Problem”, American Journal of Sociology 111(2):447–504, Sep 2005. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=8454054808294113528.

42. Martin Ruef, “Strong Ties, Weak Ties and Islands: Structural and Cultural Predictors of Organizational Innovation”, Industrial and Corporate Change 11(3):427–449, Jun 2002. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=1537882885659613748.

43. Bob Sutton, “Why The New Yorker’s Claim That Brainstorming Doesn’t Work Is An Overstatement And Possibly Wrong”, Work Matters, 26 Jan 2012. http://bobsutton.typepad.com/my_weblog/2012/01/why-the-new-yorkers-claim-that-brainstorming-doesnt-work-is-an-overstatement-and-possibly-wrong.html.

44. Isaac S. Kohane, et al, “Does Collocation Inform the Impact of Collaboration?” PLoS ONE 5(12): e14279. http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0014279.

45. In 2011, 74.6% of designers had a personal blog or web site. In 2010, 76.5% did. A List Apart, “Findings from The Survey For People Who Make Websites 2010”, calculations by the author. http://aneventapart.com/alasurvey2010/add.html. A List Apart, “Findings from The Survey For People Who Make Websites 2011”, calculations by the author.

46. Irene S. Levine, “The Friendship Doctor: The Price of Falling in Love: Losing Two Close Friends?”, Psychology Today, 16 Sep 2010. http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-friendship-doctor/201009/the-price-falling-in-love-losing-two-close-friends.

47. Apparently, even though two-thirds of us work with at least one other designer, only one-third of us will actually talk with them.

48. Ethan Marcotte, “Fluid Grids”, A List Apart, 3 Mar 2009. http://www.alistapart.com/articles/fluidgrids/.

49. Ethan Marcotte, “Fluid Images”, Unstoppable Robot Ninja, 17 Apr 2009. http://unstoppablerobotninja.com/entry/fluid-images.

50. Dan Cederholm and Ethan Marcotte, Handcrafted CSS: More Bulletproof Web Design, New Riders Press, 2009.

51. Louis Pasteur, “Discours prononcé à Douai, le 7 décembre 1854, à l’occasion de l’installation solennelle de la Faculté des lettres de Douai et de la Faculté des sciences de Lille” (Speech delivered at Douai on 7 Dec 1854 on the occasion of his formal inauguration to the Faculty of Letters of Douai and the Faculty of Sciences of Lille), reprinted in: Pasteur Vallery-Radot, ed., Oeuvres de Pasteur, Masson and Co., 1939, vol. 7, p. 131. Translated from the original French by the author, also available at http://archive.org/stream/oeuvresp07pastuoft#page/130/mode/2up.

52. The question was, “Do you still find your work exciting?” In 2011, 83% of designers answered “A lot” or “Some”. In 2010, 74.2% of designers answered “Yes - very frequently” or “Yes - frequently”. A List Apart, “Findings from The Survey For People Who Make Websites 2010”, calculations by the author. http://aneventapart.com/alasurvey2010/add.html. A List Apart, “Findings from The Survey For People Who Make Websites 2011”, calculations by the author. http://aneventapart.com/alasurvey2011/add.html.

53. Based on Amazon “Search Inside This Book” results for those terms in Handcrafted CSS, and inline search of the A List Apart and Unstoppable Robot Ninja articles.

54. One example of many: Erick Beck, “An Event Apart Recap”, Texas A&M Webmaster’s Blog, 13 Jul 2012. http://webmaster.tamu.edu/2012/07/13/an-event-apart-recap/.

55. Jeffrey Zeldman, “Boston Globe’s Responsive Redesign. Discuss.” The Daily Report, 15 Sep 2011. http://www.zeldman.com/2011/09/15/boston-globes-responsive-redesign-discuss/.

56. Balsamiq, “Responsive Design with Mockups”, Balsamiq. http://support.balsamiq.com/customer/portal/articles/615901.

57. Karen McGrane, “Adapting Ourselves to Adaptive Content (video, slides, and transcript, oh my!)”, Karen McGrane, 4 Sep 2012. http://karenmcgrane.com/2012/09/04/adapting-ourselves-to-adaptive-content-video-slides-and-transcript-oh-my/.

58. Nitasha Tiku, “Conde Nast Is Experiencing Technical Difficulties”, New York Observer, 19 Jul 2011. http://observer.com/2011/07/scott-dadich-ipad-conde-nast/.

59. Daniel Jacobson, “COPE: Create Once, Publish Everywhere”, ProgrammableWeb, 13 Oct 2009. http://blog.programmableweb.com/2009/10/13/cope-create-once-publish-everywhere/.

60. David Ogilvy, Ogilvy on Advertising, Random House, 1985, p.160. Ogilvy doesn’t cite sources, but Richard (Dick) Stanton and “split-run” references can be found in advertising trade magazines dating back to at least 1939.

61. Ibid., pp. 202-204.

62. Claude Hopkins, Scientific Advertising, 2003 Illustrated PDF by Carl Galletti, Lord & Thomas, 1923. http://www.scientificadvertising.com/scientificadvertising.pdf. The original edition of this book is now in the public domain.

63. Claude Hopkins, Scientific Advertising, with an introduction by David Ogilvy, Crown Publishers, 1966, p.7

64. Douglas Bowman, “Goodbye, Google”, stopdesign, 20 Mar 2009. http://stopdesign.com/archive/2009/03/20/goodbye-google.html.

65. Steve Jobs, “1993 interview re: Paul Rand and Steve Jobs”, YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xb8idEf-Iak&t=3m10s.

66. Rudy and Jason Fried, comments on “Behind the Scenes: A/B Testing Part 2: How We Test”, Signal vs. Noise, 2 Aug 2011. http://37signals.com/svn/posts/2983-behind-the-scenes-ab-testing-part-2-how-we-test#comment_67685.

67. Lance Jones, “Move Beyond 2% By Avoiding These 5 Testing Obstacles”, Topping Two Percent. http://www.toppingtwo.com/2012/07/27/move-beyond-2-by-avoiding-these-5-testing-obstacles/.

68. Jamie Dihiansan, “Behind the Scenes: A/B Testing Part 3: Finale”, Signal vs. Noise, 23 Aug 2011. http://37signals.com/svn/posts/2991-behind-the-scenes-ab-testing-part-3-final.

69. Jamie Dihiansan, “On the Front Lines, In the Trenches”, Signal vs. Noise, 25 Feb 2011. http://37signals.com/svn/posts/2790-on-the-front-lines-in-the-trenches.

70. Ibid.

71. Jamie Dihiansan, “Behind the Scenes: Highrise Marketing Site A/B Testing Part 1”, Signal vs. Noise, 21 Jul 2011. http://37signals.com/svn/posts/2977-behind-the-scenes-highrise-marketing-site-ab-testing-part-1.

72. Jamie Dihiansan, “Behind the scenes: A/B testing Part 3: Finale”.

73. “An artist should create beautiful things, but should put nothing of his own life into them. We live in an age when men treat art as if it were meant to be a form of autobiography. We have lost the abstract sense of beauty.” —Basil Hallward from Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, Ward, Lock and Company, 1891.

76. http://www.toysforbob.com.

77. Durrell Bishop argues persuasively for self-evidence in his interview, “Things Should Be Themselves!” Bill Moggridge, Designing Interactions, MIT Press, 2007, pp.541–548. Video online at http://www.designinginteractions.com/interviews/DurrellBishop.

78. Kevin Kelly, “Computational X”, The Technium, 7 Mar 2011. http://www.kk.org/thetechnium/archives/2011/03/computational_x.php.

80. Matt Webb, “What comes after mobile”, YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1Xe8LeTn9g.

81. Ibid.

82. Sudoku Grab. http://www.cmgresearch.com/sudokugrab/.

83. Matt Webb, “What comes after mobile”, YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1Xe8LeTn9g.

84. Adam Grossman, “How Dark Sky Works”, Dark Sky Journal. http://journal.darkskyapp.com/2011/how-dark-sky-works/.

86. Leap Motion, “Introducing the Leap”, YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_d6KuiuteIA.

87. Jeff Han, “Jeff Han demos his breakthrough touchscreen”, TED. http://www.ted.com/talks/jeff_han_demos_his_breakthrough_touchscreen.html.

89. Michael Abrash, “Two Possible Paths into the Future of Wearable Computing: Part 1 – VR”, Ramblings in Valve Time, 7 Sep 2012. http://blogs.valvesoftware.com/abrash/two-possible-paths-into-the-future-of-wearable-computing-part-1-vr/.

90. Nicholas Negroponte quoted by Bill Moggridge, Designing Interactions, MIT Press, 2007, p.515.

91. Hiroshi Ishii interviewed by Bill Moggridge, Designing Interactions, pp.526–527

92. Stu Card interviewed by Bill Moggridge, Designing Interactions, p.637

93. Mark Pilgrim, “Six”, Dive Into Mark, 9 Oct 2002. http://web.archive.org/web/20110514125529/http://diveintomark.org/archives/2002/10/09/six.

94. Matt Webb, Interconnected, 17 Mar 2011. http://interconnected.org/home/2011/03/17/finding_baby_sciences_and_new_moons.

95. On design professionalism, Andy Rutledge’s essay of the same name is a strong, opinionated read—as is his follow-up, his code of professional conduct for 2012, which you can read at http://designproacademy.org/code-of-professional-conduct.html. Mike Monteiro’s book Design is a Job hits many of the same points and some different ones, but in a different manner and from a different perspective. Both are worth your time.

For the calculations of A List Apart survey results, “designers” were considered those who responded either “Web Designer”, “Designer”, “Interface Designer, UI Designer”, or “Information Architect” to the question, “Which of the following most closely matches your job title?” in each year’s survey. In 2011, that was 2,977 of 15,707 respondents (18.95%). In 2010, that was 4,637 of 16,904 respondents (27.43%).

Bill Moggridge’s Designing Interactions and Bill Buxton’s Sketching User Experiences go into detail about the sketching exercises, prototyping techniques and user testing activities used from the invention of the GUI through the invention of near-future devices in university labs. The mouse was tested and invented the same way you’d design and test something now. Just start.